The Meeker Incident was one the final incidents in a long history of animosity between the Ute people of Western Colorado and the white settlers from the east. Here we explore the events leading up to the Meeker Incident and the Battle of Milk Creek, and the aftermath that was directly responsible for the forced expulsion of the Utes and the establishment of Grand Junction as a municipality.

Background

The Ute people of western Colorado’s oral traditions tell us that they have been here since the beginning of time. They are the only tribe in the US who do not have a migration story. Their origin story states that their creator placed them here in their native lands.

Long time ago when there were no people on earth, the Creator cut sticks and put them in a bag. He said the sticks would be people. Coyote watched secretly as the Creator cut the sticks. He did that all the time. When the Creator was away, Coyote opened the bag and out came a lot of people. They were all talking different languages and went in many directions.

When the Creator returned, there were very few people left in the bag, and he became very angry. His plans were to divide the people equally on the earth, and then he said, “Now there will be war between one another over the land.”

“The people that stayed in the bag will be brave and will never be defeated. They will be called Ute.”i

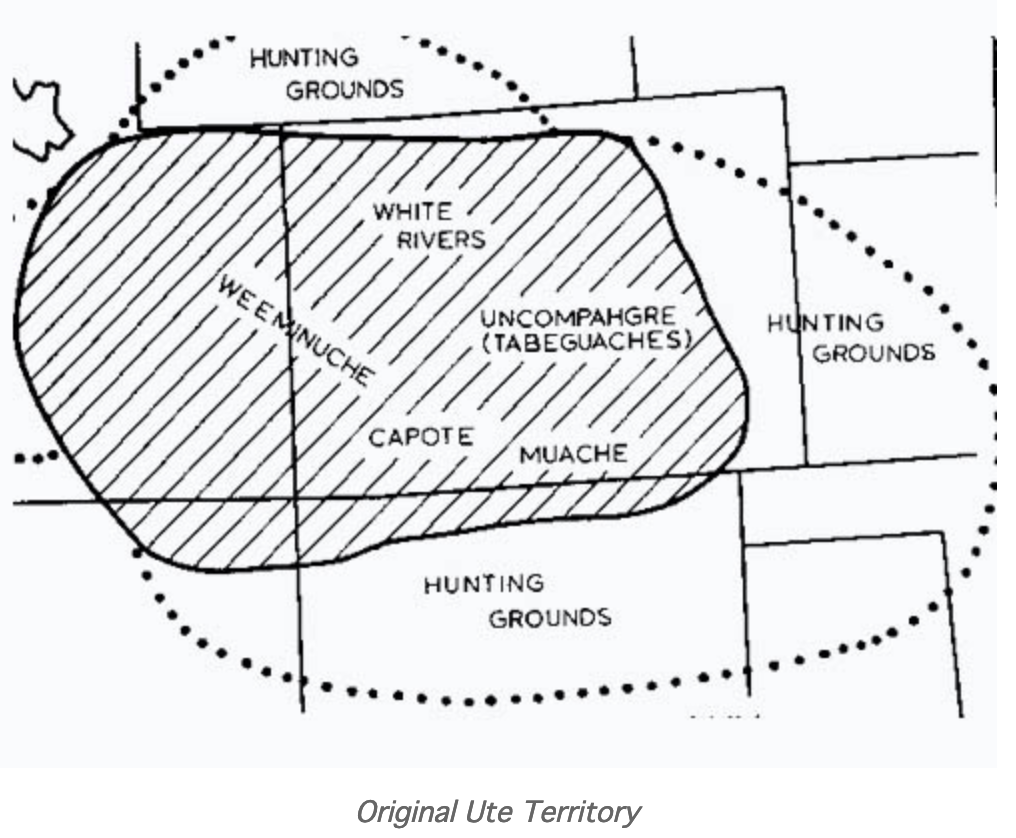

Anthropologists who study Native Americans have been able to trace the Ute people back to at least 1300 C.E. In the early days, they were made up of small family bands, that lived in seasonal locations, following the available resources. In the summers, they would break into small groups while in the winter they would band together in the lower valleys. Their territory once covered most of the state of Colorado, the majority of eastern Utah, down into parts of Arizona and New Mexico and up to the border with Wyoming. They had a reputation for being fierce warriors and expert hunters.

Life changed irrevocably in the sixteenth century when Spaniards began to colonize the land that would become New Mexico. White explorers started venturing into Ute territory. They brought with them horses, weapons, tools, new languages, diseases and new beliefs. The Utes were one of the first tribes to acquire the horse and with it, their prestige as hunters and warriors grew. The Spanish and the Utes held a begrudging understanding that the Spanish could explore as long as they didn’t settle on Ute land and the Utes could continue to benefit from the trade goods brought by the Spanish.

As the Spanish settled in, the Utes, as well as other native populations, continued to clash with settlers. They did not understand the Europeans need to own land and to expand their empires. The Utes believed that the land owned themii, not the other way around.

The tenuous understanding with the Spanish came to an end in 1848 following the Mexican-American War when the US won and laid claim to the territory once under the Spanish crown, then the independent nation of Mexico.

Shortly after the US claimed victory, the US government set about making its first treaties with the Indian nations in its newly acquired lands. The first treaty with the Utes was the Calhoun Treaty of 1849 that forced the Utes to recognize the governance of the US, to allow US citizens free passage through Ute territory and allowed for the establishment of military and trading posts on Ute land.

On December 30, 1849, the first treaty between the Utes and the United States was signed at Abiquiu, the frontier town on the Chama River north of the town of Espanola. This treaty was arranged largely by the great Indian agent, James S. Calhoun. The Utes recognized the sovereignty of the United States and agreed not to depart from their accustomed territory without permission. The Utes also agreed to perpetual peace and friendship with the United States, to abide by United States law, and to permit citizens of the United States government to establish military posts and agencies in their country.iii

This marked the beginning of a series of treaties between the Ute people and the United States, including the Treaty of 1868 that created a large reservation on the western 1/3 of Colorado for the Utes in exchange for ceding the territory east of the Rocky Mountains. This treaty was later modified by the Brunot Agreement in 1873 that removed the portion of the Ute lands that included the San Juan Mountains due to increased encroachment by miners at the time. Although the Utes lost land in the San Juans, they maintain hunting rights that continue to this day.

Nathan Meeker and the White River Indian Agency

The Treaty of 1868 not only established the boundaries of the Ute reservation where all six Colorado bands of the Ute people were to reside, it also called for the establishment of two Indian Agencies in Colorado: one at White River and the other at Los Piños. These agencies would serve as outposts where Indian Agents would distribute food and other supplies to the Ute people per the Treaty. In exchange the Ute people were to send their children to white schools and to hand over any Utes who “commit[s] a wrong or depredation” to US authorities.iv Also under this treaty, Ute people were offered a 160-acre allotment if they wished to take up farming in an attempt to persuade the Utes to adopt European customs.

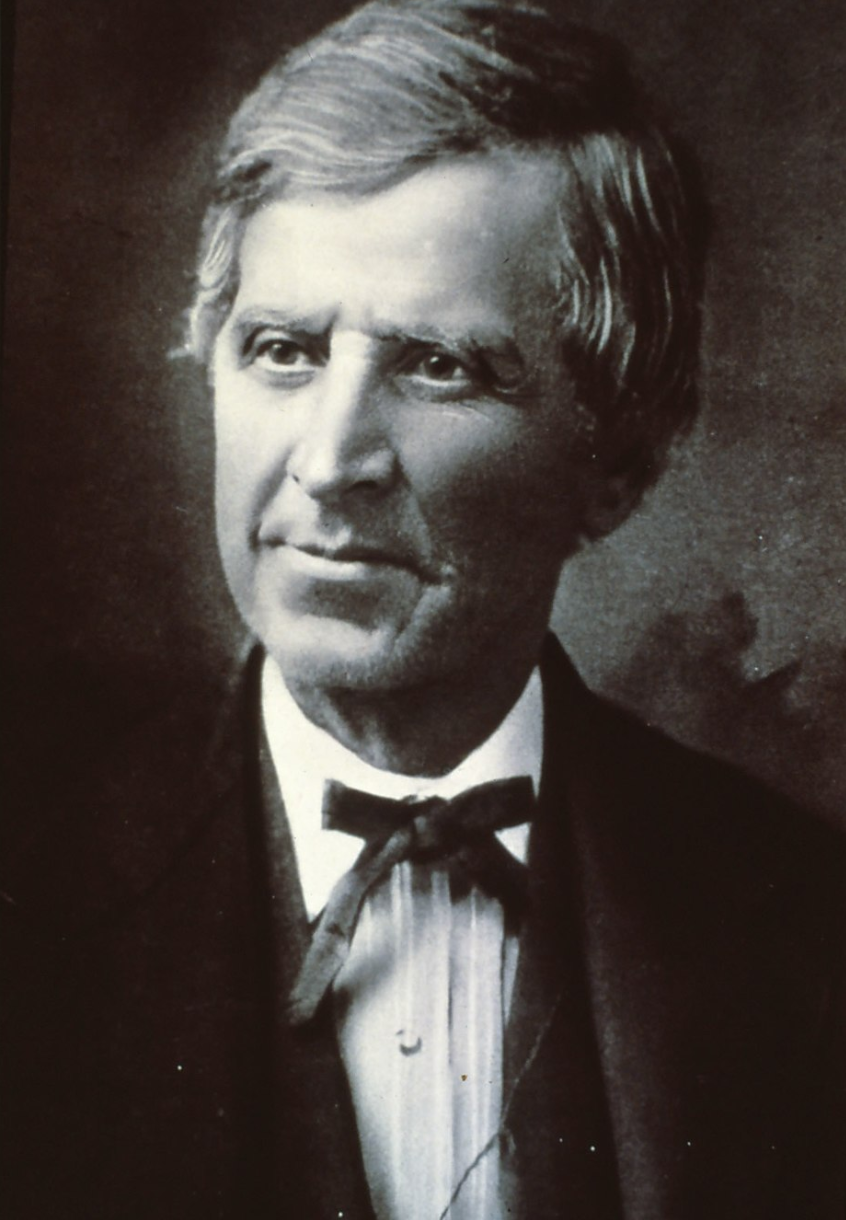

Nathan Meeker was offered the appointment of Indian Agent at the White River Indian Agency at the behest of President Rutherford B Hayes in 1877. Many sources describe him as an idealist who believed in creating a utopian agrarian society. Prior to arriving at the White River Indian agency, he had already made two attempts at creating such communities with little success. His first attempt in Trumbull Phalanx, Ohio, began shortly after he married his wife, Arvilla, in 1844 and it failed rapidly. Meeker later became a correspondent for newspaperman Horace Greely during the Civil War. Greely shared Meeker’s enthusiasm for establishing agricultural communities and provided financial backing for Meeker to establish Union Colony at what is now Greely, Colorado beginning in 1870. Union Colony had difficulties in the beginning and Meeker fell into debt.

When Meeker arrived at the White River Indian Agency in May of 1878 at the age of 61, he not only hoped to pay off his debts, but he genuinely believed he could “civilize” the Ute people who he saw as “savages” and turn them into productive members of society.v However, the Utes showed no interest in abandoning their cultural traditions and lifeways in order to adapt to a European style of living. Josephine Meeker, Nathan’s daughter, only had a few children enroll in her school and their attendance was sporadic. Nathan Meeker followed the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ policy of withholding food and supplies from the Ute people in order to force them to comply. The Utes knew this was against their treaty which became a cause of contention. Meeker also employed idle threats of calling in the military to force the Utes into adopting an agrarian lifestyle. The Utes came to deeply distrust Meeker and their requests for a replacement agent fell on deaf ears.

The Meeker Incident and the Battle at Milk Creek

Tensions came to a boiling point when Meeker determined that the location of the White River Agency was not located in a suitable place for farming and moved the agency 11 miles downriver to Powell Park. With him he brought his wife, his daughter, a master farmer Shadrach Price with his wife, Flora-Ellen and their two young children, and other working men from Union Colony to help begin farming at Powell Park.vi This was an incredibly unpopular move with the Ute people who used this lush meadow as pasture land for their prized ponies. He ordered Shadrach Price to plow the meadow, which angered the Utes and one of them shot over Price’s head while he was plowing.

Indian Agency employee, Fred Shepard, who was later killed in the incident, sent the following letter to his mother regarding Meeker plowing up the prized pastureland:

“In regards to my getting out of here soon, I have not felt if I was in any danger so far as my life is concerned since I have been here any more than ever I did in your door-yard. I don’t blame the Ute for not wanting his ground plowed up. It is a splendid place for ponies and there is better farming land, and just as near, right west of this field, but it is covered in sage brush Douglass [Quinkent] says he will have the boys [the Ute people] clear the sage brush if N.C. [Nathan Cook Meeker] will only let the grass alone. But, N.C. is stubborn and won’t have it that way and wants the solders to carry out his plans. Don’t know how it will turn out, but you can bet if they touch anybody, it will be the agent first.”vii

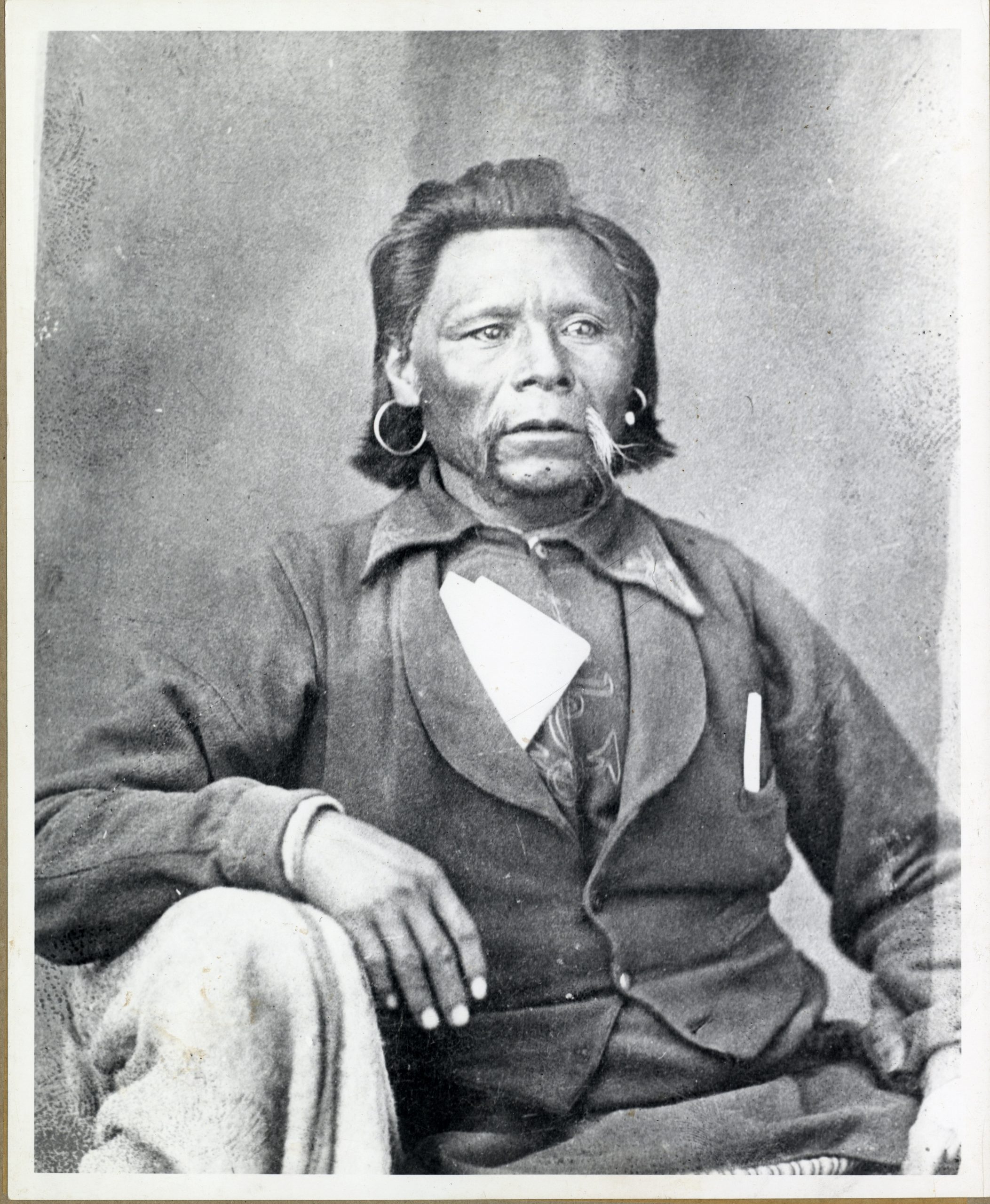

According to Meeker, a Ute named Canalla (known to the whites as Johnson), accosted him over plowing up the fields. Although the Utes denied that this happened, Meeker sent a telegram to Washington D.C. asking for military help to protect the Agency and bring the Utes under his control.

The U.S. government responded by sending Major Thornburg and his troops from Fort Steele to the White River Agency. This further upset the Utes as they viewed the reservation as their sovereign land and that any incursion by U.S. troops would be viewed an act of war in violation of the Treaty of 1868 by the Utes. Nicaagat (known to the whites as Jack) went out to meet Major Thornburg and entreat him to not enter Ute lands with his troops.

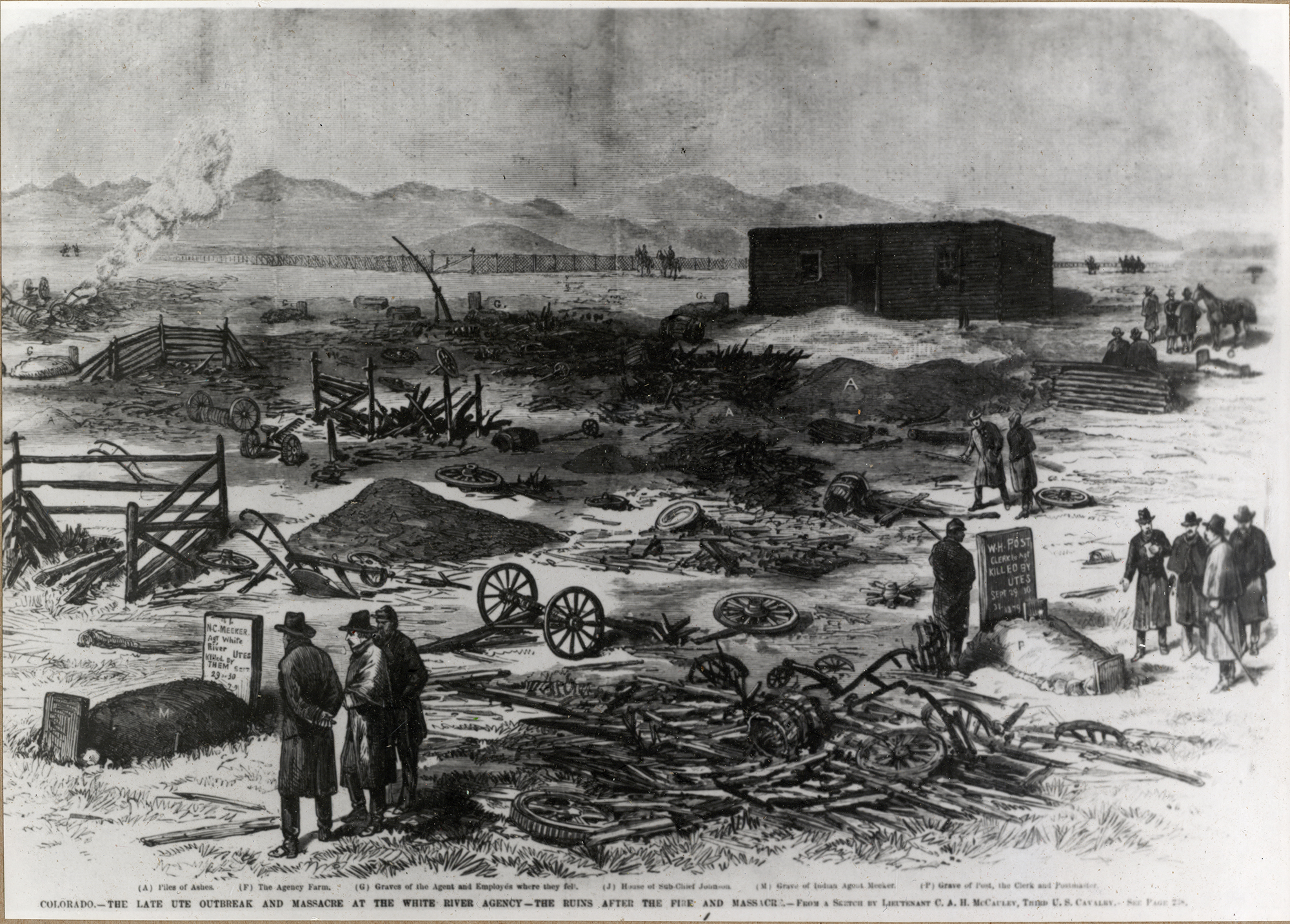

On the morning of September 29, 1879, Thornburg and his troops crossed the northern boundary of the reservation at Milk Creek. The Utes responded by pinning down the troops for days. Buffalo soldiers led by Captain Francis Dodge arrived to aid the Thornburg’s troops after his death but were unable to turn the tide. Upon the arrival of reinforcements from Wyoming on October 5th, the Utes surrendered fearing another massacre like the one that had occurred at Sand Creek.

When the soldiers marched to the White River Agency, they discovered that the Agency had been attacked, the buildings had been burned, and all eleven of the male employees, including Nathan Meeker, had been killed and their bodies mutilated. The women at the Agency, including Arvilla Meeker, Josephine Meeker, and Flora-Ellen Price with her two young children had been taken hostage by the Utes and taken to Grand Mesa. The Utes took the women and children captive in part because of cultural tradition, and in part to protect the Utes from reprisals from the army.viii

The army mobilized to track down the band of Utes that had taken the women and children. However, the captives were peacefully released in the end of October after negotiations with government agents and with the help of other Utes, including Chief Ouray. Initially the women said they were treated well by the Utes, but they later changed their story, further fomenting fear and hate towards the Utes.

Aftermath

Two separate investigations into the Meeker Incident were held—one at the Los Piños Agency in 1879 and a series of congressional hearings held the following year. Both investigations found that the army had trespassed onto the reservation, and so the Utes involved were not punished. However, public opinion in Colorado had not been favorable towards the Utes prior to the Meeker Incident, and after it only became worse. Governor Pitkin had previously called for the removal of the Utes, and this event led the Colorado Legislature to pass a resolution for the removal of the Utes and they nearly passed a bill that would have put a $25 bounty on Ute scalps.ix

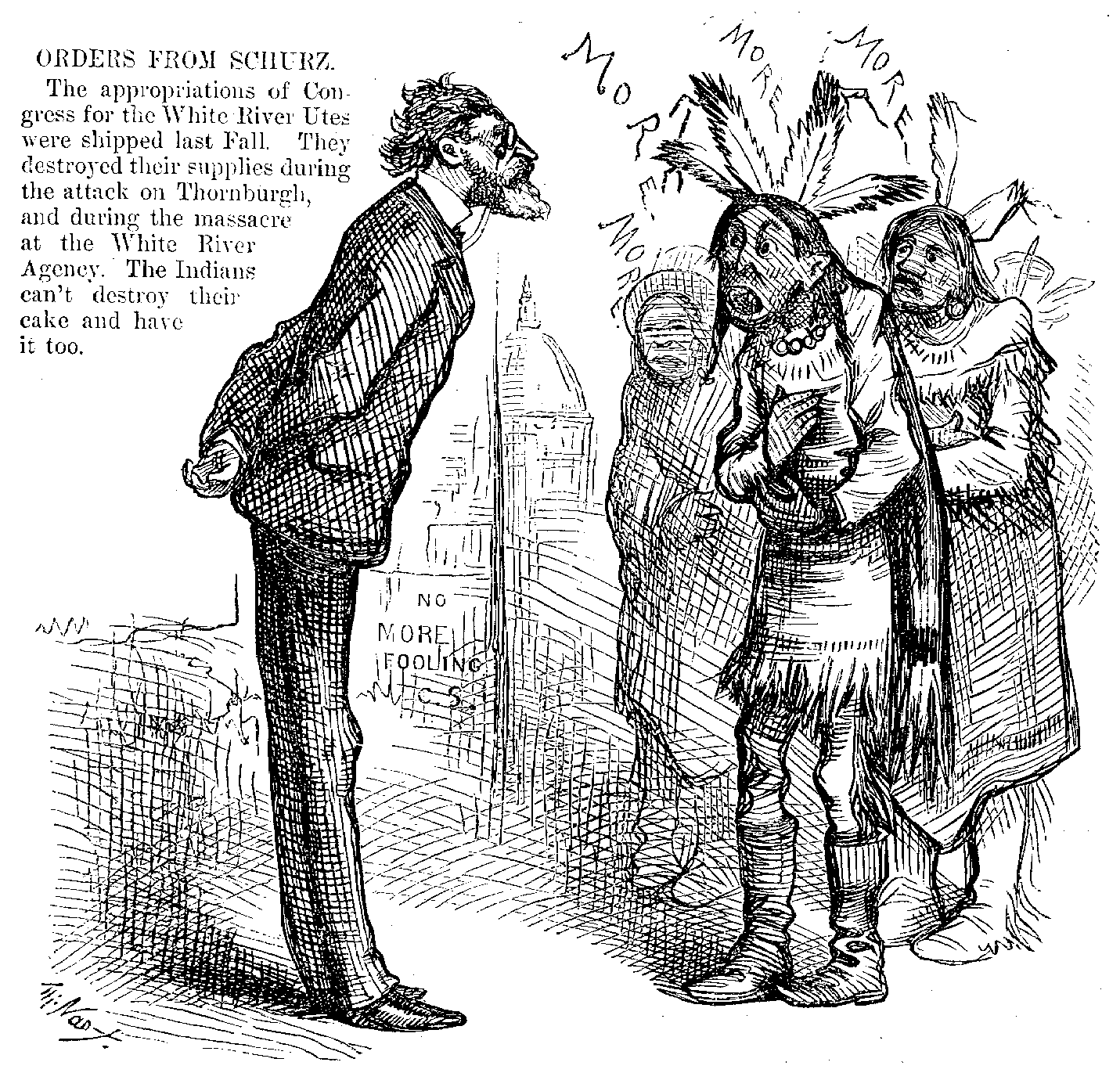

Ultimately, U.S. Secretary of the Interior, Charles Schurz, created a non-negotiable agreement, forcing the White River Utes to Utah in 1880. The following year, the U.S. Army force marched the remaining Utes to this new, much smaller, reservation. The Southern Ute and the Ute Mountain Ute were moved to smaller reservations in Southwestern Colorado. Grand Junction was founded on the heels of the expulsion of the Utes, as white settlers had been coveting Ute lands for quite some time. The townsite was staked in 1881 and was first called “Ute.” In 1882, Grand Junction was incorporated and formed a municipal government.

1Ute Creation Story, http://www.uintahbasintah.org/csute.htm, accessed 6/15/2020

2History of the Southern Ute, https://www.southernute-nsn.gov/history/, accessed 6/15/2020

3Delaney, R., J. Jefferson & G. Thompson. 1972. The Southern Utes: A Tribal History. Salt Lake City, Utah; University of Utah Printing Service. Pg. 16. https://collections.lib.utah.edu/details?id=349662#contents

4Ute Treaty of 1868 https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/ute-treaty-1868 accessed 9/9/2020

5Silbernagel, R., (2011). Troubled trails: The Meeker affair and the expulsion of the Utes from Colorado. Salt Lake City, UT: The University of Utah Press.

6The Meeker Massacre and the Battle of Milk Creek http://www.meekercolorado.com/HSociety.htm accessed 9/9/2020

7Ibid

8Silbernagel, R., (2011). Troubled trails: The Meeker affair and the expulsion of the Utes from Colorado. Salt Lake City, UT: The University of Utah Press.

9Meeker Incident https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/meeker-incident Accessed 9/21/2020