The Grand Valley has a rich geologic history that includes 225 million years of life preserved within the various rock layers that make up the area. Soon after the area was settled in the 1880s, paleontologists began arriving to investigate the mysteries of ancient life captured in the rocks. Paleontologists continue their research even today at the Museums of Western Colorado, as well as other institutions around the world, who are still unlocking the clues to the past, with new technology and new hypotheses. Discover the geology and paleontology of the Grand Valley below.

Background

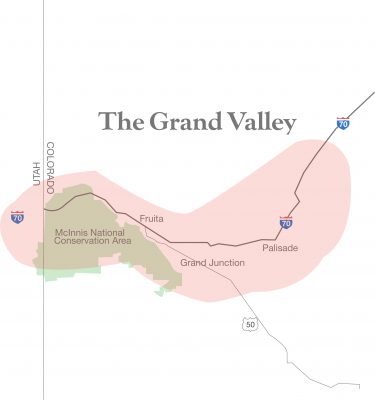

Where is the Grand Valley?

The Grand Valley includes the three major municipalities of Grand Junction, Fruita, and Palisade in Colorado. It extends from the Grand Mesa at the mouth of DeBeque Canyon in the east into Utah in the west. It is bordered on the north by the Bookcliffs and on the south by the Umcompaghre Uplift (Colorado National Monument).

What is stratigraphy?

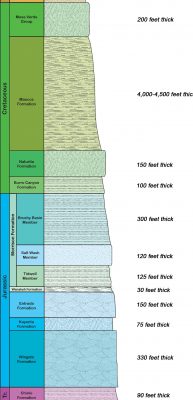

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology that is concerned with the order of and relative position of rock units and the relation of rock units to geologic time. The Principle of Superposition is used geologists when they want to determine the order in which rock units were deposited. This principle states that for any undisturbed sequence of rocks deposited in layers, the youngest layer is on top and the oldest on bottom, each layer being younger than the one beneath it and older than the one above it. Geologists illustrate the relative position of rock layers using a stratigraphic column. In this digital exhibit, we will explore the stratigraphic column of the Grand Valley (see image to the left) to learn about the different layers and the fossils contained within them.

What is a geologic formation?

A geologic formation is a rock layer or sequence of rock layers that are distinct from units above and below. A formation must be large enough to appear on the scale of regional geologic mapping. Formations can range in thickness from less than a meter to several thousands of meters.

What is paleontology?

Paleontology is the study of past life. There are a number of subdisciplines that make up paleontology. For example:

- Paleobotany is the study of fossil plants

- Invertebrate Paleontology is the study of fossil invertebrate animals such as molluscs or insects

- Vertebrate Paleontology is the study of vertebrate animals including fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals

- Ichnology is the study of trace fossils

- Paleoecology is the study of past ecosystems and climate

- Taphonomy is the study of what happens to an organism from the time it dies until it is discovered.

Paleontology differs from archaeology which is a subdiscipline of anthropology, focusing on humans and the artifacts they leave behind.

Geologic Time in the Grand Valley

To make sense of Earth’s 4.56-billion-year history, geologists have divided time into segments that include the following (ranging from largest to smallest): eons, eras, periods, epochs, and ages. These time divisions are not equal; however, they are based on changes or major events in Earth’s history.

The Phanerozoic Eon is marked by the appearance of visible life, hard-bodied organisms that readily left a fossil record behind. It is divided into three eras: Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic. The eon that precedes the Phanerozoic is called the Proterozoic. The oldest rocks in the Grand Valley date from the Proterozoic Eon, while the majority are from the Phanerozoic Eon. We are currently in the Phanerozoic Eon, the Cenozoic Era, the Quaternary Period, and the Holocene Epoch.

Grand Valley Stratigraphy and Paleontology

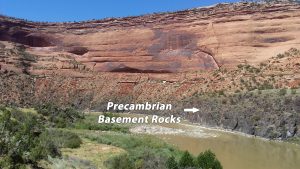

Precambrian (2.2 billion years ago (Ga) – 700 million years ago (mya))

The oldest rocks in the Grand Valley are from the Proterozoic. They are gneiss and schist. Schist is formed when igneous or sedimentary rocks are put under pressure at high temperatures over a large area for a long period of time. Gneiss is created when those same rocks are subjected to temperatures and pressures higher than those needed to make schist. These conditions make it impossible for any fossils to be preserved. If there was primitive life in the Grand Valley in the Precambrian Time, we have no record of it.

Click photos to enlarge.

The Great Unconformity

Part of Earth’s story is missing from the Grand Valley! In fact, it is missing from most of the American West. A huge gap exists in the rock record between the Precambrian and the next layer of rocks – the Chinle Formation. This gap is called an unconformity. An unconformity exists where rocks were either not deposited or they were deposited and later eroded before new rocks were laid down. Unconformities are common throughout the rock record. This one spans over one billion (1,000,000,000) years!

The Mesozoic Era

Most of the Grand Valley’s rocks are from the Mesozoic Era. This is the time in Earth’s history when dinosaurs rose to dominate the planet which is why it is sometimes called the “Age of Dinosaurs.” The word means “Middle Life” because it is the Era between the Paleozoic and the Cenozoic. Despite being from the same era, the Mesozoic rocks in the Grand Valley were deposited in a variety of different environments

Chinle Formation (237 mya – 201.3 mya)

The Chinle Formation, represented by the red rocks at the base of the cliffs in Colorado National Monument, was laid down by streams and lakes on a vast floodplain that extended from what are now Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona, up into northern Utah and even Idaho. 203 million years ago. When these rocks were being deposited, this area would have looked very different and would have been populated with creatures you might not recognize today.

Although Triassic Period is also known as the beginning of the “Age of Dinosaurs,” we have not yet found any early dinosaur bones in western Colorado. Instead, in the Late Triassic-age Chinle Formation, we find footprints of dinosaurs and fossils of giant, fish-eating amphibians and crocodile-like animals that lived here when western Colorado was close to the equator and the region was covered by rivers, lakes and forests.

Click photos to enlarge.

Wingate Sandstone (201 mya – 199.3 mya)

After the Chinle Formation had been deposited, a massive desert began taking over the area. At the same time, western Colorado, along with the rest of North America, began moving further away from the equator. Also, occurring during the time that the Wingate Formation was being deposited, the Earth underwent the End-Triassic Mass Extinction–one of Earth’s five major mass extinctions! Climate change brought on by volcanic activity tied to the beginning of the breaking apart of the great supercontinent of Pangea is believed to be responsible for the major drop in biodiversity that saw extinctions both in the sea and on land at this time. However, this event also paved the way for dinosaurs to dominate the landscape. Tracks of animals that lived in the desert are common in the Wingate.

Click photos to enlarge.

Kayenta Formation (199.3 mya – 182.7 mya)

The Kayenta Formation was formed after rivers began cutting through the older sand dunes, creating oases between the dunes for ancient life. In Colorado the Kayenta Formation is relatively thin and shows mainly dunes. In Arizona, this rock layer is very thick and preserves lots of river channels, and we find dinosaurs like Dilophosaurus, as well as early mammals, turtles, and frogs.

Click photos to enlarge.

Entrada Sandstone (165 mya – 164 mya)

As climate conditions changed, the rivers slowly dried up and sand dunes moved back into the area. This orange-red sandstone gets its color from the iron oxide coatings between the grains, and is the remnant of this large sand desert. Look closely at the walls of sand and you will see the sweeping and crisscrossing layers, called cross-bedding, of the fossil sand dunes. The arches of Arches National Park are formed in this layer. The only vertebrate animal found from this formation is the crocodile relative Entradasuchus.

Click photos to enlarge.

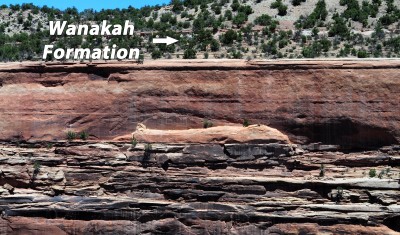

Wanakah Formation (164 mya – 163 mya)

There is another unconformity between the Entrada and Wanakah Formations. The Wanakah was deposited on the edge of a salty lake located in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado. Fossils are not common, but dinosaur tracks and invertebrates have been reported.

Morrison Formation (156.3 mya – 146.8 mya)

The Morrison Formation is a widely distributed rock unit found in the western United States. It is exposed in Colorado, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Wyoming, Montana, South Dakota, and Nebraska. The sediments that make up the Morrison Formation were deposited by rivers draining mountain ranges to the south and southwest, as well as floodplains salt flats, and ponds. These mountain ranges were low and wide but may have caused a rain shadow making the region somewhat arid. However, groundwater and the rivers flowing from the mountains kept the area well vegetated. The variety of ecosystems of Morrison Formation would have been similar to the Mississippi River Valley, but in a wet-dry seasonal climate. It is known for iconic dinosaurs, such as Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, Brachiosaurus, Stegosaurus (the Colorado State Fossil), Allosaurus, and Ceratosaurus (the Official Dinosaur of Fruita). Its rocks are colorful and show many layers that can be read by geologists and paleontologists to interpret the past.

If you want to learn more about fossils found in the Morrison Formation see: Famous Fossil Sites of the Grand Valley

Click photos to enlarge.

Cedar Mountain/Burro Canyon Formations (132 mya-99 mya)

These two names refer to the same group of rocks. The specific name used depends on if you are north or south of the Colorado River. The sediments from this formation were deposited by rivers, lakes, and on floodplains. Once again there is missing time in the rock record: the Morrison Formation is Late Jurassic, but the Cedar Mountain/Burro Canyon is late Early Cretaceous. The fossils in the Cedar Mountain Formation are different than those found in the Morrison. Include animals like Utahraptor, Cedarpelta, Cedarosaurus, and Gastonia (named for a Grand Valley resident); however, these animals have been only found in the Moab area. In the Grand Valley, fossil plants and scraps of dinosaur bone have been found.

Click photos to enlarge.

Naturita Formation (113 mya – 93.9 mya)

The sandstones, shales, and coals of the Naturita Formation were formed along rivers and beaches near the coastline of the ancient inland sea, the Western Interior Seaway. Sometimes called the “Dinosaur Freeway”, the 150-foot thick rock unit preserves some of the most extensive and detailed tracks found in western North America. Burrows and ripple marks are also commonly found in this rock unit. Once widely called the Dakota Formation, scientists now recognize that the Dakota Formation found west of the Rockies is not the same as the Dakota Formation found in the Great Plains –they are actually two wholly different rock units that were given the same name. The term Naturita Formation is now being used by most scientists and will eventually replace the use of Dakota Formation in Utah and Colorado where it still lingers on interpretive signs and in older books.

Click photos to enlarge.

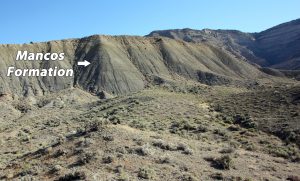

Mancos Formation (93.9 mya – 85 mya)

The dark grey and beige slopes along the base of the Bookcliffs are formed by the Mancos Formation. This rock unit is over 4000 feet (1220 m) thick and composed predominantly of carbonaceous shales, with occasional sandstone units. The Mancos was deposited in a quiet, deep water (up to 1000 ft!) environment during the Late Cretaceous Period. Fossils of clams, ammonites, sharks, fish, and marine reptiles are often found in these rocks. This sea is called the Western Interior Seaway, and it advanced and retreated several times during the Cretaceous Period. At its greatest extent, the Gulf of Mexico was connected to the Arctic Ocean, dividing North American in half. Scientists refer to eastern continent as Appalachia and the western continent as Laramidia.

Click photos to enlarge.

Mesa Verde Group (85 mya – 72 mya)

The Mesa Verde Group forms the cap of Mount Garfield and the Bookcliffs. It is a 200-foot thick sequence of sandstones and mudstones that were deposited near ancient seacoasts during the Late Cretaceous Period. After deep water of the Mancos Formation receded, the shallower water environments of the Mesa Verde Group were deposited. The repeating sequences of muds and sands show the changing water depth and changing coastlines of the Western Interior Seaway during this period. Dinosaur tracks and fossils have been found in these shallower units, along with fossils of plants, crocodiles, mammals, turtles, and fish. The Mesa Verde Group is the last rock unit in the Grand Valley to be deposited during the “Age of Dinosaurs”.

Not preserved in the Grand Valley is the End-Cretaceous Mass Extinction event that wiped out all dinosaurs except birds 66 mya. This event also wiped out flying and swimming reptiles, and important marine invertebrates. There are multiple lines of evidence to suggest that an asteroid as big as 6 miles across struck the planet near what is today the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico. This impact would have created an enormous cloud of dust and debris that would have limited sunlight and thus disrupt the food chain. Also occurring at the time was increased volcanism in present-day India that may have also altered the climate, and a massive, sudden drop in sea level that would have crashed plankton populations, disrupting the ocean food web.

The Cenozoic Era

The End-Cretaceous Mass Extinction ushered in the Cenozoic Era that continues through to today. The Cenozoic Era is sometimes referred to as the “Age of Mammals” because it was during this time that mammals diversified and radiated, eventually becoming the animals we are familiar with today. Rock units from the early part of the Paleocene Epoch, which is also the earliest part of the Cenozoic, are not present in the Grand Valley, but can be found further south in New Mexico. Either deposition did not occur, or erosion stripped away the evidence.

Wasatch (DeBeque) Formation (65 mya – 53.5 mya)

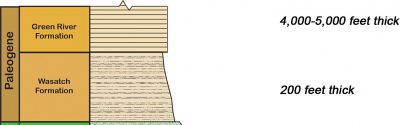

Locally referred to as the DeBeque Formation, the Wasatch Formation represents a rich river ecosystem during the late Paleocene Epoch to the early Eocene Epoch. Formed of colored mudstones and sandstone beds, the Wasatch Formation is nearly 200 feet thick and creates striking maroon and white badlands along Interstate 70 between DeBeque and Parachute, Colorado. Fossils found in the Wasatch Formation include snails, crocodiles, birds, turtles, and mammals.

Click photos to enlarge.

Green River Formation (53.5 mya – 48.5 mya)

The light grey Roan Cliffs near Douglass Pass that rise up behind the Bookcliffs are composed of the Green River Formation. This formation is the remnants of an extensive freshwater lake system made up of three lakes—Fossil Lake, Lake Uinta, and Lake Gosiute (of these, Lake Uinta covered the Grand Valley) that stretched from the Colorado and Utah north to Wyoming during the Eocene Epoch, 50 million years ago. The Green River Formation is composed of shales, oil shales, and limestones. Fossils are common in these rocks. The gentle preservation has preserved exquisite detail in fossil insects, leaves, skates, fish, birds, and small mammals. The oldest bat fossils on Earth are even found in Green River limestones. Although the region was at the same latitude as it is today, the planet was much warmer at the time. The plant fossils and fossil animals like crocodilians can only survive in areas where there is a constant warm temperature, indicating that the climate was subtropical 50 million years ago.

Click photos to enlarge.

Ice Age Deposits

Gravel deposits and conglomerates from glacial outwash are also present in the Grand Valley. These deposits formed as the last glaciers in the region melted, sending floodwaters down existing waterways. Locally sourced “river rock” for landscaping is often taken from these deposits. Remnants of ice age animals such as Columbian mammoths, horse, and bison have been found in the Grand Valley.

Click photos to enlarge.